Why young Aussies are ‘Generation F***ed’ and doomed to have it worse than any others in history

Written by admin on June 17, 2024

A stark summary of what life is like for young adults in Australia these days amid the soaring cost-of-living, housing crises and economic inequality has gone viral.

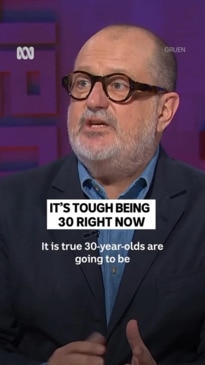

A sharp and to-the-point assessment of the “extremely difficult” situation facing Millennials, delivered by Russel Howcroft, an advertising guru and panellist on the hit ABC series Gruen, painted a bleak picture.

“It’s the hardest it’s ever been … in history for a 30-year-old in Australia,” Mr Howcroft said on the show last week.

“It’s true that 30-year-olds are going to be less well off than their parents. That’s a fact.”

A big driver of the generational difference is the rapid growth in house prices, which have surged by more than 380 per cent at a national level since 1992.

Mr Howcroft revealed that when he was 30, the house he purchased cost roughly three times his annual salary.

“Now, [it’s] eight times plus for a 30-year-old,” he said.

“That’s what it’s going to cost you to get into the housing market.”

The cost of repaying a HECS debt after completing university has also doubled in the past 15 years, shackling young people with hefty burdens well into their working lives.

“[It has] gone from a $15,000 bill to a $30,000 bill,” he said.

“And it’s true that a Baby Boomer paid half the tax … when they were 30, that a 30-year-old now pays. So, it’s extremely difficult.”

The clip has been shared multiple times across social media, with comments flooding in from young Aussies who are feeling the struggle.

“Luckily my rent is going up fifty bucks a week ‘due to cost of living’, so my landlords that own our whole block can survive these hard times,” one wrote.

Another said: “Boomers took the ladder with them on the way up.”

“So we doing anything to fix this yet? Or still just talking about it?” one quipped.

But some didn’t accept Mr Howcroft’s argument and put the blame for tough times squarely on the shoulders of Millennials themselves.

“We Boomers didn’t have $6 coffee to go or $25 smashed avo brekkies, we took lunch from home and fish n chips with potato cakes was our weekend splurge.”

Experts say that kind of simplistic counterpoint is flawed and misses the bigger picture that on virtually all measures, young Aussies today have it worse than any previous generation.

Life is harder than ever

Prominent economist Danielle Wood, chair of the Productivity Commission and former chief executive of think tank the Grattan Institute, detailed the rough economic hand young people have been dealt.

Delivering the Giblin Lecture late last year, Ms Wood said the cost-of-living crisis and high inflation had added a short-term burden to much longer term systemic issues.

“Australia’s young people are navigating a cost-of-living crisis with less economic fat, and with the major policy tools to respond to inflation stacked against them,” she said.

“For today’s young people, the slow-burn issues of an education system under pressure, unaffordable housing, a climate crisis, and growing government indebtedness loom large.”

She said the economic and social systems young people find themselves existing within has prioritised the needs of older generations – “sometimes by accident and sometimes by design”.

The perception that young people are frivolous with their money, prioritising smashed avocado toast over financial responsibility, is flawed, Ms Wood said.

In fact, young people are spending less than older generations did at that point in their lives on non-essentials, with “all the growth in spending … because of essentials”.

Despite being more educated than those young people who’ve come in generations before, Millennials aren’t necessarily earning more.

Since the start of the century, real wages have flatlined for young Aussies.

Economist and author Alison Pennington, who penned the book ‘Gen F’d? How Young Australians Can Reclaim Their Uncertain Futures’ last year, said young people “feel the terrible weight of a society that is failing them”.

“Existential doom and mass disempowerment are taking a grip on young people’s thinking,” Ms Pennington wrote in analysis for The Conversation.

“They’re trying to make the right choices against a backdrop of collapsed collective movements and government inaction against an energised global fossil fuel sector.”

A sense of economic excuse comes with “lifelong consequences” in terms of employment, health and general wellbeing, she said.

“It’s unsurprising that many young people have given up.”

A ‘Jane Austen world’

Those pundits who believe the mammoth transfer of wealth that’s set to come when Baby Boomers fall off the perch are also ignoring important context, Ms Wood said.

It’s true that most of the country’s record $14.8 trillion in household wealth is held by older Aussies, meaning “there is an awfully big pot of wealth to be passed on”.

But those who’ll benefit most have already won “the birth lottery”.

“Among those who received an inheritance over the past decade, the wealthiest 20 per cent received on average three times as much as the poorest 20 per cent,” she said.

“The Productivity Commission projects that among current retirees, just 10 per cent of all inheritances will account for as much as half the value of bequests.”

Thanks to medical advancements and higher living standards, those lucky enough to receive a decent inheritance from mum and dad will likely be seeing that money later in life.

“The most common age to receive an inheritance is late 50s or early 60s – much later than the money is needed to ease the midlife squeeze of housing and children that [Millennials] face,” Ms Wood said.

“Large intergenerational wealth transfers can change the shape of society. They mean that a person’s economic outcomes relate more to who their parents are than their own talent or hard work.

“French economist Thomas Piketty has warned of a ‘Jane Austen world’ where inequality is exacerbated by ever-growing inheritances.

“Easing intergenerational inequality means policies that work for the whole generation, not just those lucky enough to have a private safety net.”

The rise of ‘Generation Rent’

Some people point to the flawed stereotype that young Aussies would rather ‘live large’ than buckle down and save a deposit for a house.

But the reality is that securing a piece of the so-called Great Australian Dream has never been harder.

Up until the late 1990s, home prices grew at about the same pace as wages, meaning most people were able to keep up with market shifts.

But between 1992 and 2018, the cost of property exploded to the tune of three times the pace of wages growth.

The impact of that widening gap is clear.

“Since World War II, Australia has been a nation of homeowners,” Ms Wood said.

“Home ownership rates peaked at more than 71 per cent in 1966. Almost three-quarters of the nation was on the property ladder and living the dream – home ownership was celebrated as an indicator of success, security, and quality of life.

“Ownership rates declined very gradually in following decades but then sharply since the early 1990s, when house prices and incomes started to diverge.”

Across the board, homeownership rates are now at their lowest levels since the mid-part of the last century.

“But what has been particularly striking is the drop among young people,” Ms Wood said.

“In 1981, when the Boomer generation was settling down and having families, 68 per cent of 30-34 year-olds owned their own home. In 2021, the equivalent figure was 49 per cent.

“The falls have been particularly pronounced for poorer, younger people, challenging the suggestion that plummeting ownership rates reflect different preferences of today’s young people.”

Young Aussies aspire to own their own home just as much as previous generations did, but the ability to do so is only achievable for “the richest young people or the ones with the richest parents”, she said.

As a result, the time it takes to scrape together a deposit has surged from about seven years in the early 90s to more than 12 years these days.

And the cost of repaying a mortgage is painfully high thanks to larger loan sizes and the Reserve Bank’s run of interest rate hikes.

“Next time your Boomer uncle regales you with horror stories about 17 per cent interest rates of the early 90s, it’s worth reminding him that six per cent rates today are as painful as the 17 per cent rates then for the typical borrower,” Ms Wood pointed out.

All of these factors combined mean the proportion of young Aussies who rent the home they live in is high – and many will be in the rental market for their entire lives.

More hurt on the horizon

Things only look set to be worse for those Aussies coming hot on the heels of Millennials.

Research by the Pew Institute in 2022 found an overwhelming majority of people across the country believe children growing up today will be financially worse off than their parents.

And it seems they’re well aware of the dire situation facing them.

Late last year, a survey of young Aussies conducted by Scape for its Gen Z Wellbeing Index found one-in-three reported struggling with their mental health and two-thirds have trouble sleeping.

When probed on what’s keeping them up at night, 78 per cent said the cost-of-living was a major concern while 67 per cent are worried about housing affordability and skyrocketing rents.

Those issues ranked higher than concern about climate change at 60 per cent.

Similarly, the latest National Youth Mental Health Survey by headspace asked young people to name their top three concerns.

More Coverage

The top three issues identified were financial instability, cost of living, and housing affordability.

“When asked to describe how worried they were about their ability to one day afford their own home, 71 per cent of participants reported they were fairly worried or very worried, while 61 per cent told headspace they were fairly or very worried about the cost of rent,” the research found.

As a result, more than half of respondents aged 18 to 25 were hesitant about the idea of one day having children because of cost pressures.