‘People have a right to develop’: Solar farm boss hits back after neighbours slam $200 million project

Written by admin on October 20, 2024

The boss of a solar farm company has hit back after neighbours slammed a “monstrous” $200 million proposal they fear will ruin their idyllic rural views and pose safety risks, saying “people have a right to develop”.

The proposed 150-megawatt solar farm and battery energy storage system in Bairnsdale, three-and-a-half hours east of Melbourne in the Gippsland region, has drawn the ire of some locals who have raised concerns about visual amenity, fire safety and the impact on surrounding properties.

Michael Wickfeldt, 62, whose 86-acre hobby farm with sweeping views of the Victorian Alps neighbours the proposed site, last month spoke out about the prospect of being surrounded by nearly 170,000 solar panels and a “monstrous” 10-acre battery.

The Bairnsdale solar farm, located on Andersons Lane next to the Moormurng state forest, is one of eight major Victorian projects being developed by BNRG Leeson, a joint venture between Dublin-based BNRG Renewables and Melbourne’s Leeson Group, which has a pipeline of more than 500-megawatts of solar farm projects across the country.

The 176-hectare project will be considered for approval by Victoria’s Department of Transport and Planning (DTP) in coming months under the state’s Development Facilitation Program (DFP), announced in March, which controversially stripped communities of their traditional rights to appeal renewable energy facilities through the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT).

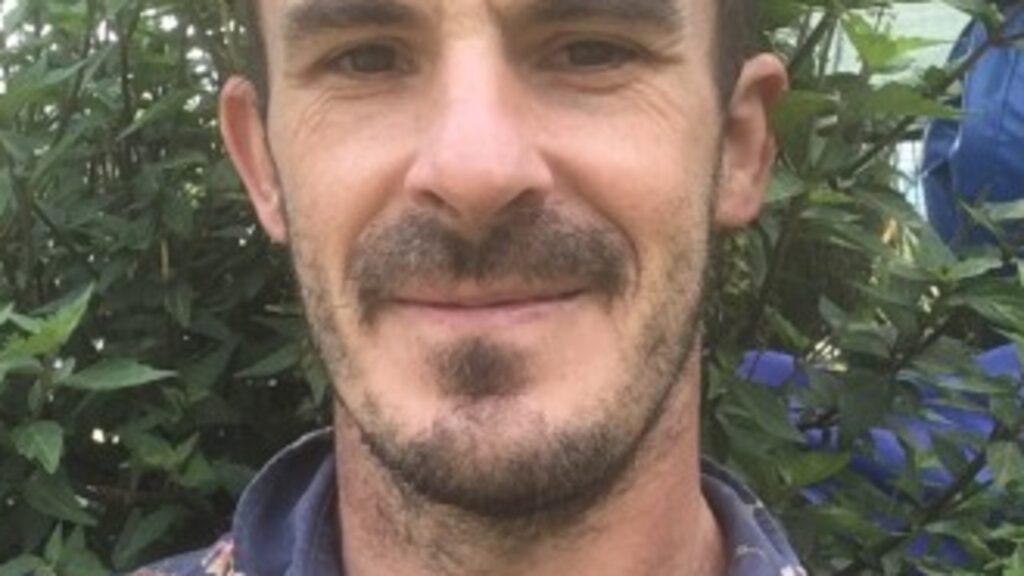

BNRG Leeson director Peter Leeson, in an interview on Wednesday, said he accepted that the visual impact was often the biggest hurdle for such projects but that opposition typically came from a “small group” of people directly impacted.

“It is a good question and it is the basis of a lot of animosity in communities that live right next door,” he said.

“You might see one kilometre away no one really objects, they see the environmental benefits, the economic benefits. Further away in the town centre [people are even more supportive]. It’s known there are going to be objections and visual amenity is the big concern. We do a lot to mitigate that, we invest heavily in the landscape screening as part of our permit requirements.”

Landscape screening generally consists of four rows of plants and shrubs spaced 1.5 metres apart.

“It’s nine metres deep of evergreen shrubs of various [height] levels, it’s a very dense screen for that visual impact you might have,” he said.

BNRG Leeson representatives met with Mr Wickfeldt to “get a feel for the aspect of the house” and as a result “completely modified the layout of the project and removed a significant amount of panels from his view”.

The concession meant the energy generation and thus project revenue would be reduced, according to Mr Leeson, who said it highlighted that the firm communicated “well with all the community and wider groups and redesign projects” to accommodate any concerns.

“This project is down the end of a long road that has minimal direct neighbours,” he said.

“We’re not selecting [sites] on the urban fringe, we’re on low-value agricultural land which has grid connection, which doesn’t have significant impacts on the environment, doesn’t have significant planning triggers, the ability to be flexible with the design. A lot of work has gone into identifying this site, which is much better than other sites around Australia.”

BNRG Leeson also downplayed fire safety concerns, saying “thermal runaway” incidents were extremely rare and the battery contained in-built fire suppression systems.

A number of design changes have been made following a meeting with the Country Fire Authority (CFA) Specialist Risk and Fire Safety Unit, which reviewed the proposed project plan.

Mr Leeson said it was “no longer a cowboy’s game of what it was 10 years ago” when often neighbours only found out about solar farm projects once a development permit had been granted.

“People think they have no avenue to object, which isn’t true,” he said.

“There’s still a public notification, people can still object and we’re expected to address any concerns. The [VCAT] appeal rights aren’t there anymore … I don’t know if that’s really made things better or easier for us because you don’t want people feeling oppositional at the outset because of something like that. There’s still avenues for people to shape the project.”

Asked whether the community should have the right to stop, rather than just shape such projects, Mr Leeson said, “Should it stop them, though? That’s the question. I think people should have a right to say what happens in their neighbourhood, but people also have a right to develop. We also have a need to develop.”

He insisted “ultimately we do need more renewable energy in Australia” to replace end-of-life coal-fired generators.

“The world’s warming, we need to implement more renewables,” he said.

“If we tie up these projects for three to four years in VCAT hearings, it’s going to cause significant delays.”

BNRG Leeson is expected to lodge its planning application within the next six weeks.

Members of the community will have the opportunity to make formal submissions to the department once the application is lodged.

Announcing the DFP earlier this year, Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan said the accelerated renewable energy pathway would “cut the red tape holding back projects that provide stronger, cheaper power for Victorians”.

More than one in five applications had ended up in VCAT since 2015, tying up a pipeline of around $90 billion worth of renewable energy projects which would create 15,000 jobs, according to the Victorian government.

“The current system means that important projects can be tied up for years seeking approval,” Ms Allan said at the time. “It delays construction and deters investment, and instead of spinning turbines, we’re too often left spinning our wheels.”

In August, Planning Minister Sonya Kilkenny approved the first renewable energy project under the new streamlined process.

The planning application for the 350-megawatt Joel Joel Battery in the Northern Grampians, which will be the largest in Australia, was fully processed in just nine weeks.

Emma Germano, president of the Victorian Farmers Federation, said last month that renewable energy facilities “have gone from being something that communities welcomed to completely losing social license on the basis that there is little or no consultation with the community”.

“The state government has taken away the community’s avenues to question projects and the impact on the environment, which includes landholders — particularly on adjoining landholders, who are often forced to be the buffer of a renewable energy zone without being compensated,” she said.

“Five years ago we were saying it’s great farmers have the opportunity to diversify their income. What we’re seeing now is inappropriate developments impacting neighbours and complete disregard for agricultural production.”

Aussie TV legend Catriona Rowntree, host of Nine’s Getaway, has previously accused the Victorian Labor government of trying to “sneak through” projects, saying in August she was shocked to learn of a proposal for a massive battery next to her farm in Little River, southwest of Melbourne.

Paul Tabone, from Gormandale in Victoria’s east, similarly had a five megawatt solar farm project next door approved despite lodging an objection.

More Coverage

“When I learned it was right next to my place, I was shocked,” he told the ABC in July.

“I thought, ‘What, right next to me? Why would someone want to put a solar farm on good grazing property to start with, and right next to a residential home?’ It’s been a kick in the guts — I’m disheartened.”